The Importance of Flower Painting

MOAH-Flora

Artweek.LA; June, 2015

According to the Book of Genesis, human beings lived in harmony in the Garden of Eden until they transgressed against God's dictates. As punishment for their hubris, Adam and Eve were banished from Paradise. One of the earliest narratives from Western Culture, the Genesis tale of The Expulsion from Eden explains man's separation from nature as retribution for his innate sinfulness. The Ancient Greeks shared the biblical belief that humans are separate from nature: Aristotle wrote of the human/nature divide in his Generation of Animals, Book IV, arguing that man is the pinnacle of creation and therefore deserves to dominate and control the natural world.

Whatever its religious, mythic, or ideological source, the belief that humans are inherently (or deservedly) separate from nature has produced a deeply entrenched conceptual polarity which has resulted in the erasure of many species as well as troubling changes in the weather. How can we reverse this long-held and imminently destructive pattern of thought?

One way is with positive images of the natural world. To represent is to create meaning; what is represented determines and is determined by what is valued. In our predominantly visual culture, where the invisible is not valued, inserting depictions of the devalued into the visual field can serve to revalue them.

Such revaluation is one of the functions of the stunning "Flora" exhibition currently on view at the Lancaster Museum of Art and History. The seductive allure of flowers and other flora is frequently represented in the exhibition. As are fauna, especially honeybees, the fragile creatures needed to pollinate so many plants. To walk through the exhibition is to be reminded of the resonant beauty of nature. The powerful depictions engage us and draw us into connection, reminding us that we are not separate from nature. Rather, we are integral parts of the biosphere. By extension, we are--all of us--diminished every time nature is threatened or damaged.

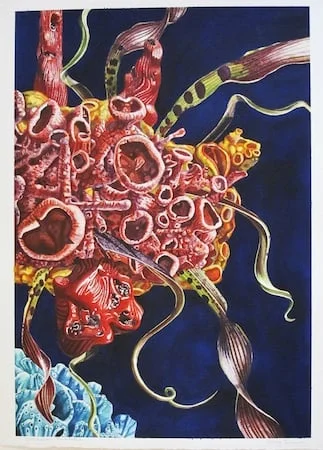

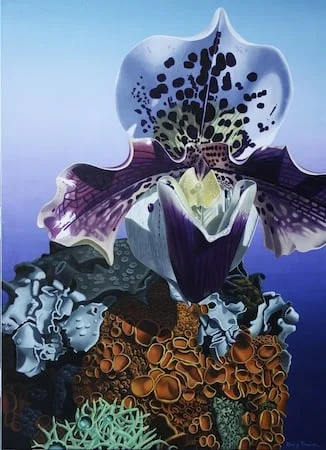

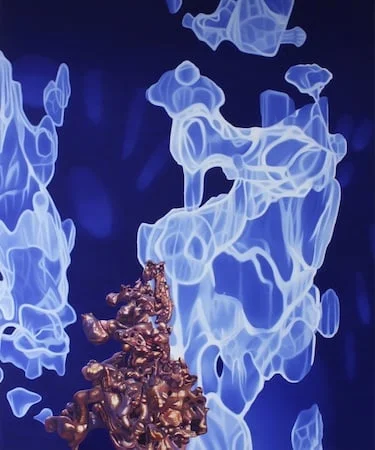

The artists in the "Flora" exhibition, and the media in which they work, are intriguingly diverse. Alphabetically, the participants are Terry Arena, whose delicate drawings of bees are scattered over the whitewashed lids of plastic food packaging; Gary Brewer, whose spectacular paintings (image above)range from the cosmic (black hole emanations) to the miniature (a nugget of copper or the exotic blossom of an orchid, exploded to human size); Mud Baron, whose home grown flowers are gathered into abundant head bouquets; Debi Cable, whose florescent paintings transform a large gallery space into a black-lit playground; Candice Gawne, whose amoeba-like glass and gas sculptures shimmer and dazzle; and Nancy Macko, whose billboard-scaled photograph of a wild-flower-filled meadow reminds us of the eco-zones in which bees flourish. The final two artists in this alphabetical listing--Lisa Schulte and Jamie Sweetman--both create art that works against the culture-nature divide. Schulte does so by wrapping ribbons of neon light around branches of driftwood. Sweetman's drawings, technically as precise as medical illustrations, pair human anatomical fragments with botanical renderings: bones and thistles, hearts and thistles. Reaching across conceptual categories, the Schulte's sculptures and Sweetman's drawings urge us to abandon separation in favor of inclusion.

Nancy Macko's powerful installation reminds us that beehives and buildings are both animal-made shelters, more similar than different. Macko constructs wooden octagons and covers them with images of and quotations about bees, allowing her own art to echo the bee-created structures of honeycombs. Her incorporation of natural forms into the cultural practice of art production serves to embrace both ends of the nature-culture polarity.

When asked how his work related to nature, Jackson Pollock is reported to have said, "I am nature." Macko and the other "Flora" artists might claim the same unification. And they might agree with Albert Einstein, who asserted, "Our task must be to free ourselves by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature and its beauty." At another time, Einstein added, "Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better."

Looking deeply into the representations of nature in the "Flora" exhibition allows us to understand that we have not been expelled from Eden. Our natural world is paradise; we are eternally connected to it, and must value and protect it as we value and protect ourselves.

--By Betty Brown

Kerry Kugelman; Art Blog, June, 2015

MOAH FLORA

In another tour de force exhibition, Andi Campognone transformsLancaster Museum of Art and History (MOAH) into a bouquet of visual offerings with FLORA, showcasing a wide swath of artwork finding its source and inspiration in the world of plants and their familiars.

Nancy Macko's multi-layered installation about bees works both as a paean to the integral and harmonic role that bees play in the larger sphere of activity that affects us, and as a call to action about the very real crisis facing the bee and the food chain it supports. Echoing these concerns, Terry Arena's exquisite graphite studies of bees, executed on food cans painted white, convey a fragility, urgency, and even the sorrow that attends the bee die-off.

The Wells Fargo gallery blossoms with Gary Brewer's perennially luscious oil paintings of floral, coral, and organic materials. Illuminated by an unseen supernal light, eclectic arrangements of forms seem frozen in space, and are rendered in detailed, rich tones that amplify the regal demeanor of each composition. Enriching the mix are new works, luminous forays into imagining the skeins of dark matter that comprise most of the universe as we know it.

In Brewer’s hands, dark matter dons a lighter guise, seemingly emanating rather than absorbing energy. Against a radiant cobalt blue field, soft lattices of diaphanous white forms seem to hover fluidly, as though suspended in water. Eschewing the hard-edged naturalism of the still-life paintings which he has more often shown, Brewer’s dark matter embodies a translucence which intrigues and delights.

In the South Gallery, Debi Cable's “Glow,”a sprawling, immersive installation of flora and fauna depicted in fluorescent paint (think “black light”) and 3-D registration is overwhelming in its scope and intensity. It’s as though we’re seeing the world though the visible light range of another species. Punctuating the ultraviolet bath are Candice Gawne's mesmerizing glass sculptures, pulsing seductively with electrified tendrils of noble gases (those gas elements excited by an electrical current, like neon, krypton, and argon). Amid Cable’s enveloping, glowing garden, Gawne’s flickering artworks are a visual attractant as much as any flower.Lisa Schulte's wood and neon sculptures take a long view in their meditations on time, transience, and renewal.

Jamie Sweetman's gorgeous drawings of biotic systems never fail to thrill in their intricacy and depth, blending the elegance of a naturalist’s rendering with intriguing layering and overlays; her visual inquiries of plant and human physiology, and their similarities, are revealing on many levels.

The East Gallery hosted a special exhibit from Dr. Bruce Love, anthropologist, showcasing artifacts and a historical overview of Antelope Valley culture over the last several millennia. Much as artwork does, this exhibition collapses time to yield new perspectives on the familiar and the invisible.

-Kerry Kugelman